Cape Cod Life Annual Guide, 2017

What would compel the Emperor of Japan, visiting the United States to shore up post-war relations between the two countries, to include a side trip to Woods Hole? Pretty much the same thing that brings visitors from all over the world to Woods Hole: science.

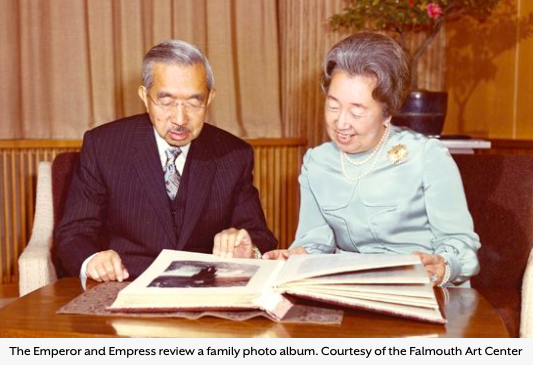

During a two-week trip to the U.S. in 1975 with his wife, Empress Nagako, Emperor Hirohito of Japan made a short detour to this Falmouth village to visit the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL).

“His being in Woods Hole was a tribute to science,” says M. Patricia Morse, professor emerita of biology at the University of Washington and co-founder of the E.S. Morse Institute at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories. A native of Woods Hole, Morse was biology professor at Northeastern University at the time, and was present at MBL when the emperor visited. “It was well known in marine biological communities that the emperor was active in marine biology,” Morse adds. He was an expert on hydroids, small creatures related to jellyfish and corals—a passion that stemmed from time spent during his childhood at his family’s imperial resort in Japan’s Sagami Bay, according to Hirohito’s obituary in The New York Times on January 7, 1989. The emperor wrote several scientific papers, including Some Hydrozoans of the Bonin Islands (1974) and Five Hydroid Species from the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea (1977).

In the summer of 2016, the Woods Hole Historical Museum hosted an exhibit celebrating the connections between Woods Hole and Japan. Coordinated by museum director Jennifer Gaines (who has since retired) and museum archivist Susan Witzell, the exhibit featured photos and documents showcasing the careers of Japanese scientists with connections to Woods Hole, and the knowledge of the ocean they shared together during the last 150 years. The exhibit included photos of Hirohito’s October 1975 visit and samples of the types of organisms he viewed while touring Woods Hole’s scientific facilities.

Emperor Hirohito uses a microscope at WHOI’s Redfield laboratory. Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Hirohito, or Emperor Showa, as he is referred to posthumously, ruled Japan during World War II. During the U.S. occupation of Japan immediately following the war, he was vilified and stripped of his divine status under Japan’s new constitution. When the imperial couple visited Falmouth, Hirohito was 74 years old, the empress, 72.

The groundwork for the 1975 trip was laid the year before when then-President Gerald Ford, who was visiting Japan, invited the emperor and empress to come to the United States. According to documents on the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library website, the Japanese people were slightly nervous about this visit. They knew that an imperial Japanese visit to the U.S. would eventually take place—and they knew it had to go off without a hitch. Relations between the former adversaries had only just reached a high point, since the end of U.S. occupation in 1952. The emperor’s only other visit to the U.S. had occurred in 1971 during a stopover in Anchorage, Alaska, when then-President Richard Nixon had flown out specifically to meet with him. This meeting was seen by the Japanese as political opportunism on Nixon’s part, according to an analysis of the visit published in the March 7, 2013, Japan Times. The 1975 visit would be symbolic of the new U.S.-Japanese relationship, and the Japanese longed to make it a success, with no politics involved, as indicated by documents on the Ford Presidential Library website.

According to news reports at the time, the emperor came to Falmouth not merely to see the world-class facilities at MBL and WHOI, but to partake in science there. As an expert on hydroids, Hirohito was aware that WHOI’s senior scientist, Dr. Howard Sanders, had discovered a new phylum of hydroids while a graduate student at Yale University.

The Japanese spent an entire year in planning the visit. The emperor’s grand chamberlain and vice grand chamberlain, key figures in the agency that oversees the imperial household’s affairs, flew out numerous times during the year, mapping out the territory and deciding what security measures to take.

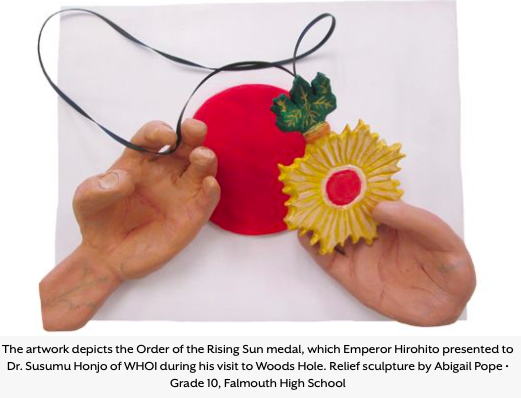

Dr. Susumu Honjo, WHOI professor emeritus, remembers when he first got word that the emperor wished to visit Woods Hole. “I received a letter from the grand chamberlain!” Honjo recalls. “I showed that letter to [WHOI director] Paul Fye, and he nearly fell off his chair.” Fye asked Honjo to personally arrange the visit. “I was the middle person, between the Japanese and the American diplomats,” Honjo continues. “And I was so young, only an associate scientist at the time.” In 2003 Honjo, who is now 83, was honored by the Japanese government with the Imperial Order of the Rising Sun for his research on the transfer of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the ocean’s interior and his efforts to strengthen Japan’s role in the international ocean science research community.

Honjo says that the vice grand chamberlain came every couple of months to prepare for the emperor’s visit. A special trip for the empress, who was active in the arts, was also planned: She would visit the Sandwich Glass Museum, the Dan’l Webster Inn, and the Falmouth Artists Guild.

On October 4, 1975, a specially marked Japan Airlines jet, around the size of a DC-10, flew into Otis Air Force base, according to former Bourne selectman and Korean War veteran Jerry Ellis, who is now 82 and lives in Sagamore. During the Korean War, Ellis’s squadron was stationed in Japan, and during a stop at one island, Ellis had the chance to see the emperor and empress, who had come to visit the American troops. “I didn’t get to take a photo though,” Ellis recalls, “because there was suddenly an alert. So when I heard the empress would be in Sandwich, I was determined to get that photo.”

Ellis’s friend, the late Bill Richardson, had property in Sandwich that abutted Otis, and Ellis got to watch the emperor’s airliner touch down while seated on the hood of his pickup truck on Richardson’s property. The white jet had been newly painted and had red markings on it, possibly the emperor’s insignia, Ellis says. “It was a beautiful plane.”

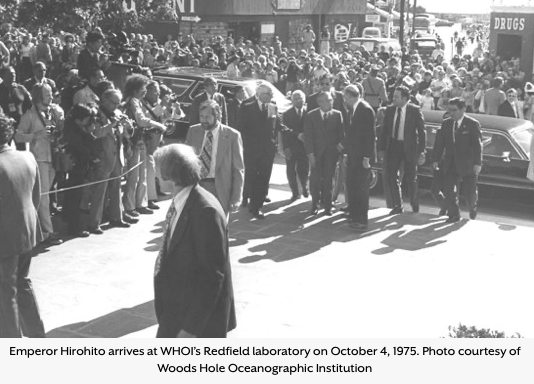

The emperor’s motorcade of eight or nine cars arrived in Woods Hole around 2 p.m., according to Don Rhoads, a Yale geology professor who was on sabbatical and staying at a friend’s house in Woods Hole. Rhoads watched the motorcade as it proceeded up Millfield Street and turned right onto School Street. He remembers it well. “My two boys were very young, and they were all wide-eyed about seeing Hirohito. His motorcade turned the corner right in front of where we were staying, and you could see his head in the car. We waved to him, and he gave us a nice wave back. It was quite a thing to see him in person.” After retiring from Yale in 1986, Rhoads started a seafloor mapping company, Marine Surveys Inc., later known as Science Applications International. He sold the company in 2000 and currently lives in Falmouth.

When the emperor and his motorcade arrived, police and security guards were stationed on the roof of the Lillie Building at MBL, while about a dozen protesters lined the lawn near the sundial across Water Street protesting Japanese whaling. Some 20 to 25 Japanese dignitaries and reporters escorted Hirohito to the welcome ceremony held in the building in his honor. An elaborate tea had been prepared for after the ceremony, but the emperor surprised everyone and said, “Let’s just get to the science,” according to Dr. Shinya Inoue, MBL professor emeritus of biology, who was present for the ceremony. Scientists scurried and quickly rearranged themselves.

“The emperor didn’t come to have tea, he came to have science!” recalls Inoue, who invented the polarized light microscope, and later, the video microscope. Inoue came to the U.S. from Japan in 1948 to attend Princeton University, and later became a U.S. citizen. In 2010, the Japanese government honored him with the Order of the Sacred Treasure, for his scientific contributions and promoting cooperative research between Japan and the United States. In September 2016, he published his autobiography, Pathways of a Cell Biologist. A resident of Falmouth, Inoue will celebrate his 96th birthday in January.

Scientists escorted the emperor to a room they’d prepared for him—a makeshift laboratory in the library catalog room. In fact, numerous concessions were made for the emperor’s visit. “I remember Howard Sanders’s lab,” Rhoads recalls with a laugh. “They were all fishermen, and they always had their poles just lined up against the wall. Well, to clean up for the visit, Sanders got all new fishing racks built for him.”

Inoue recalls that when the emperor looked through his monochromatic polarized light microscope, he asked, “How come one can see so well?” It was the only microscope of its kind at the time, patented by Nikon and American Optical, Inoue says. “I explained to him that the microscope uses a special kind of polarized light, so things show up that you can’t normally see.” Through the lens of Inoue’s microscope, the emperor got to see specimens he was familiar with through an entirely new light, and specimens he’d never even heard of. “It was a special occasion,” says Inoue.

“Dr. Inoue allowed us to see chromosomes, and the emperor was very impressed,” says Morse. Japanese newsmen, who had traveled back and forth in the months before the visit, shot photos of the occasion for publication in Japan. “It was fun to see real genuine Japanese news people in such great numbers,” adds Morse.

Meanwhile, the Sandwich Glass Museum was also teeming with Japanese reporters, as Empress Nagako arrived there in her own motorcade. According to the Sandwich Historical Society’s November 1975 newsletter, The Acorn, the empress was quiet, soft-spoken, and intensely focused on all the pieces she saw. She seemed regretful when the vice grand chamberlain gestured that it was time to go, the newsletter notes.

Ellis, still hopeful about getting a photo, arrived just in time to see the empress coming out of the museum. He watched from the green in front of the Sandwich Town Hall directly across from the museum entrance. “It was thrilling to see an empress here in little Sandwich,” he says. “There was a lot of Secret Service. I happened to have glanced up at the bell tower of the First Church of Christ, and there were two Secret Service guys up there with binoculars. I said to my friend, ‘If those guys are up there, there’s got to be more of them around that we can’t see.’” Even with the security forces, Ellis got his photo that day.

The empress spent about 30 minutes at the museum, according to The Acorn. From there, she was taken via limousine to The Dan’l Webster Inn for a brief rest, reports an article in The Lowell Sun on October 5, 1975. A small Japanese doll encased in glass in the lobby commemorates the visit. The empress then stopped by the Falmouth Artists Guild, and her visit there was highlighted in the art center’s recent 50-year anniversary celebration.

The emperor and empress spent a mere two hours on Cape Cod before being whisked away from Otis Air Force Base to continue on their U.S. tour. But the visit left a lasting impression on those fortunate enough to have witnessed it.

A native Cape Codder, Marina Davalos is a freelance writer who lives in Cotuit.

Hokule’a is coming!

The beautiful replica of an ancient Polynesian double-hulled sailing canoe will sail into Vineyard Haven Harbor on June 28, then heads to Woods Hole, arriving July 1.

The East Coast of the United States is the 19th leg of the Hokule’a’s 3-year Malama Honua (Caring For Our Earth) Worldwide Voyage. The Hokule’a departed from Hilo, Hawaii in May of 2014.

The Hawaiian vessel’s mission is to weave a “lei of hope” by sharing the stories of men and women working hard to achieve a sustainable way of life. Hokule’a’s voyage, says world renowned oceanographer Dr. Sylvia Dr. Earle, “is bringing attention to all those who are inspired by the positive message that we can achieve great things if we do what we can to save the planet – and we do it together.”

On her way up the East Coast, the Hokule’a will be in New York on June 8 to commemorate World Oceans Day with United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon.

“I am honored to be a part of Hokule’a’s Worldwide Voyage,” the Secretary General said. “I am inspired by its global mission. As you tour the globe, I will work and rally more leaders to our common cause of ushering in a more sustainable future, and a life of dignity for all.”

The Hokule’a’s unprecedented voyage of hope is extra special because she circumnavigates the globe without the use of modern instruments. Her construction in the early 1970s sparked a cultural revival throughout Polynesia. Back then, there were only a handful left on the planet skilled in the art of wayfinding: navigating solely by the stars, ocean swells and marine life.

One of them, a traditional navigator named Mau Piailug, from the tiny Micronesian island of Satawal, was the link to this revival, as he imparted his knowledge over decades of training to a group of Hawaiians. Nainoa Thompson is one of them and he is now president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, based in Honolulu.

Stops on Hokule’a’s worldwide voyage include Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia, Madagascar, South Africa, Brazil, Cuba, Florida, Virginia, Washington D.C., and New York. Her crew is meeting with educators and first peoples to discuss a sustainable future for our planet.

“We have to teach our children at a young age to connect with nature,” Thompson said.

— By Marina Blythe Davalos